Alain G. Cribier, MD

Hospital Charles Nicolle, University of Rouen, France

The history of interventional medicine is short with an explosion of innovative treatments emerging at the end of the 20th century and dramatically expanding in the 21st century. For the younger generation of interventional specialists, with the armamentarium of these strategies at their fingertips, it is intellectually impossible to imagine what it was like treating cardiovascular disease less than 50 years ago. For those of us who were witnesses to that period and the developments that followed, it was another world.

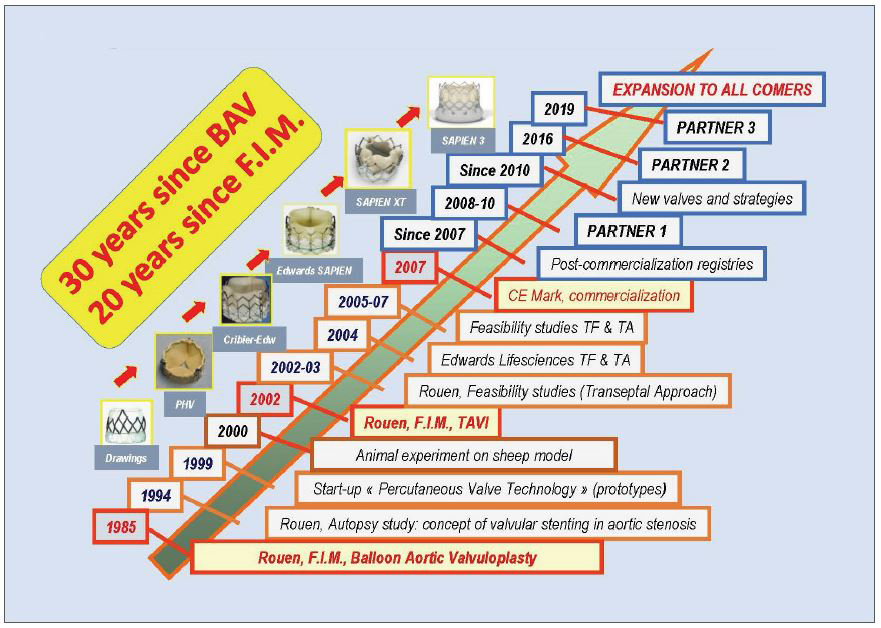

The treatment of aortic stenosis (AS) is the most prevalent acquired valvular disease, and the first successful implantation of an aortic stented valve in a human, performed on April 16th 2002, is celebrated the 20th anniversary. But before the development of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), non-coronary heart diseases, along with their dedicated interventional techniques, saw rapid growth from the transcatheter treatment of congenital pulmonic stenosis in 1979 and aortic valvular stenosis (AVS) in 1983, mitral valvuloplasty in 1984, and balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) in 1985. In September 1985, faced with a 72-year-old female patient with calcified AS, recurrent syncope, and imminent death, the team at Rouen University Hospital adapted an existing technology from the field of congenital valve disease. Under local anaesthesia, a pulmonary balloon was employed to dilate the patient’s aortic valve using a percutaneous transcatheter femoral approach. This first-in-human BAV led to an immediate haemodynamic and clinical improvement, followed by relief of symptoms and a return to normal life for the patient. However, after several years it became evident that balloon dilatation was not a long-lasting solution due to early valvular restenosis in 80% of patients at one-year follow-up. The merciless criticism to the failure of BAV reinforced a resolution to find a viable solution to deal with the issue of aortic valve re-stenosis. Remarkably, this technique knew re-birth with the onset of TAVI since it is used in daily practice to predilate the native valve or post-dilate the prosthesis.

The concept of implanting a dedicated stented valve for calcified AS was born out of this challenge. All BAV balloons could fully expand the calcified aortic valve despite the calcification. The idea that emerged was to maintain the initial positive results of the expansion by implanting a stent with a valve inside using the diseased native calcified valve as an anchor. This concept posed other issues besides the nature of the diseased native valve itself. Critical questions arose concerning the immediate proximity of essential anatomical structures: above, the coronary ostia and below, the mitral valve insertion, and the His bundle at the upper part of the interventricular septum. In Rouen, a landmark intensive, in-depth research with autopsies validated the concept of valvular stenting in AS. With my colleague, Helene Eltchaninoff, we did validate the correct dimensions of the stented valve to ensure there would not be damage to the surrounding structure, a key step to guarantee the feasibility and safety of the concept. The stents were strongly anchored within the calcified valve structures, thus decreasing the risk of secondary device embolization.

In 2002, the first-in-man implantation of this revolutionary device could be performed as a last resort option in a 57-year-old male patient, with severe AS on a very calcified bicuspid valve. He was dying, in cardiogenic shock, with a 12% left ventricular ejection fraction. He had severe comorbidities, including lung cancer, acute ischemia of the leg by occlusion of an aortofemoral bypass, and a floating thrombus into the left ventricle. For these reasons, he had been turned down for surgical valve replacement despite his age. Against all odds, we could successfully perform this first TAVI case using an unplanned highly challenging transeptal approach since the femoral arteries were not usable. This was followed by a breath-taking clinical improvement. The case reported in Circulation hit the headlines. The technique then expanded first in our center with 38 patients treated on a compassionate basis, then in a few centers in Europe and the USA. In 2005, a total number of 100 patients had received TAVI. The turning point was the acquisition of our start-up by Edwards Lifesciences in 2004, leading to an evolution in the technology that continues to this day. A valve size of 26 mm was added, and a steerable delivery system was created to allow an easier and safer transfemoral approach. This approach was pioneered by John Webb in Canada. In 2005, there was the launch of a concurrent TAVI system, the self-expanding CoreValve later acquired by Medtronic, which played an incontestable role in the fabulous expansion of TAVI worldwide. Rapidly many technological improvements were made year after year, with the development of new TAVI systems, new approaches, lower profile devices, and preventive solutions against paravalvular leaks. Consequently, the simpler and safer transfemoral approach progressively turned into the standard strategy for TAVI, used in more than 90% of patients, leading to a ‘democratisation”’ of the procedure and contributing to the burst of implantations worldwide (Figure 1).

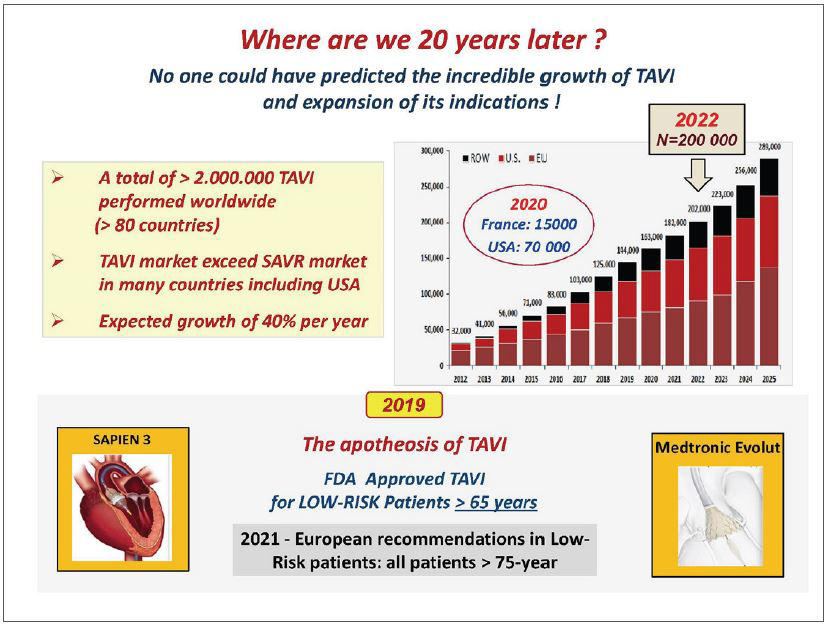

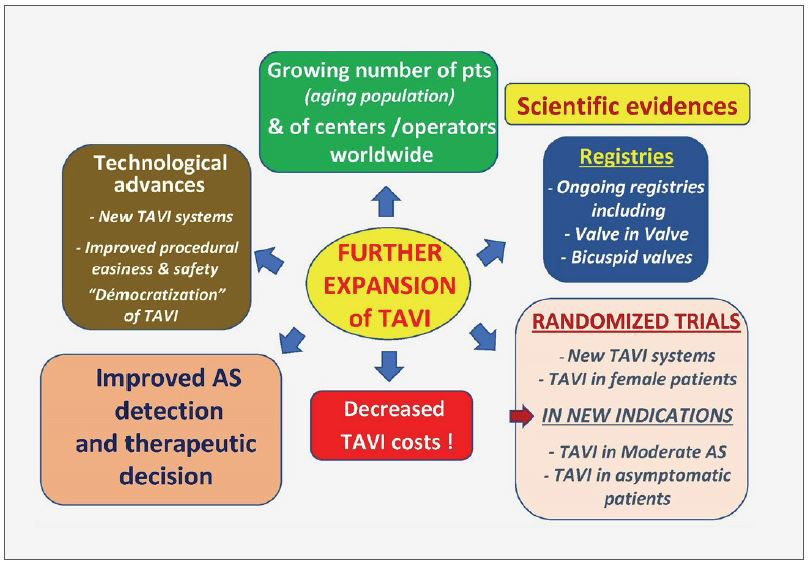

In parallel with the advanced models of TAVI systems, a careful process of staged evidence-based medicine led to the proof that a treatment, originally limited to ‘compassionate’ use in high surgical risk patients, could be enlarged by the American and European guidelines to include patients at intermediate risk and finally, in 2019, to low surgical risk patients as well. The acute and long-lasting non-inferiority or superiority of TAVI over surgery was consistently demonstrated on many main or secondary endpoints, more particularly death and stroke rates. The number of patients who benefited from TAVI is now reaching two million, in over 80 countries. In numerous countries, the number of TAVI procedures now exceeds the number of surgical valve replacements (Figure 2). How can be seen the future of TAVI? A continuous expansion of the procedure can be predicted, in the range of 10% per year for several reasons: 1) The aging population, whereas aortic stenosis is typically a disease of the elderly, earlier detection of the disease by regular practitioners. 2) The continuous improvement in technology which has notably increased the safety of the procedure. 3) A growing experience of the individual operators leading to an increase in the number of specialized centers practicing TAVI. When combined, experience and accessibility have made TAVI an easy procedural choice where in the past cardiac surgery would have been the only option. 4) The continued expansion of indications to low-risk younger patients provided that the long-term durability of the implanted valves will be fully demonstrated. This has encouraged research on other types of valves than those made of the pericardium, less prone to deterioration. 5) The continued and future expansion of TAVI to other indications, such as valve-in-valve procedures (such as treating future TAVI dysfunction) or the treatment of moderate AS in patients with heart failure or asymptomatic patients with severe AS. 6) Also, importantly, the increase in TAVI procedures and the vital competition between devices should lead to an overall decrease in the cost of TAVI which is of particular interest for lower-income and developing countries. 7) And of course, the outstanding combination of excellent clinical results and the simplicity of the procedure for the patients themselves: no sternotomy, the use of local anaesthesia, a short hospital stay, and, most importantly, a rapid return to normal life without the need for rehabilitation.

This steady expansion is an excellent example of successful translational research, and moving findings from concept to bench, bench to bedside, feasibility trials to larger clinical registries, and evidence-based trials to everyday practice. The constructive dialogue that continues between multidisciplinary physicians and engineers has been central to the evolution of TAVI. However, it is of interest that TAVI, unlike PCI, began with the most untreatable of patients and only now is being used in lower-risk groups (Figure 3). In the advances in the treatment for valve disease TAVI played - and continues to play - a seminal role. Looking back over the last 20 years since that first TAVI, we are astonished by the impact this procedure has had. TAVI crystallized the study of structural heart disease, inspiring a younger generation of interventionalists and scientists. It remains an innovative and disruptive technology influencing many of the ways that medicine is practiced today. In cardiology alone, it paved the way for percutaneous transcatheter treatment of the mitral and tricuspid valves, has led to far-reaching developments in cardiac imaging, and has been instrumental in bringing together specialists in the Heart Team concept. After 20 years, the future stories of TAVI are still being written.

Hot Topics

Game of Thrones, TAVR vs. SAVR

Sunday, May 7, 4:10 PM - 5:30 PM

Valve & Endovascular Theater, Vista 1, B2

Edited by

Jon Suh , MD

Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital Bucheon, Korea (Republic of)