Lots of interesting abstracts and cases were submitted for TCTAP 2023. Below are the accepted ones after a thorough review by our official reviewers. Don’t miss the opportunity to expand your knowledge and interact with authors as well as virtual participants by sharing your opinion in the comment section!

TCTAP A-005

Association Between Smoking Habit Changes and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction After Acute Ischemic Stroke

By Dae Young Cheon, Myung Soo Park

Presenter

Dae Young Cheon

Authors

Dae Young Cheon1, Myung Soo Park2

Affiliation

Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Korea (Republic of)1, Hallym University Dongtan, Korea (Republic of)2

View Study Report

TCTAP A-005

Acute Coronary Syndromes (STEMI, NSTE-ACS)

Association Between Smoking Habit Changes and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction After Acute Ischemic Stroke

Dae Young Cheon1, Myung Soo Park2

Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Korea (Republic of)1, Hallym University Dongtan, Korea (Republic of)2

Background

Stroke is one of the leading causes ofdisability and death, and its prevalence and morbidity tend to increase as we enteran aging society. It is also known that myocardial infarction (MI) occurs notinfrequently after ischemic stroke (IS) and both diseases share risk factorsand similar strategies for secondary prevention. There are continuousdevelopments in secondary prevention methods for MI and IS, emphasizing usingmedication and lifestyle modification, including smoking cessation. However, whetherchanges in smoking habits before and after the diagnosis of IS affects the riskfor myocardial infarction remain unclear. Thus, we aimed to investigate theimpact of smoking habit change on the risk of myocardial infarction in theischemic stroke population using the Korean National Health InsuranceServices(K-NHIS) Database.

Methods

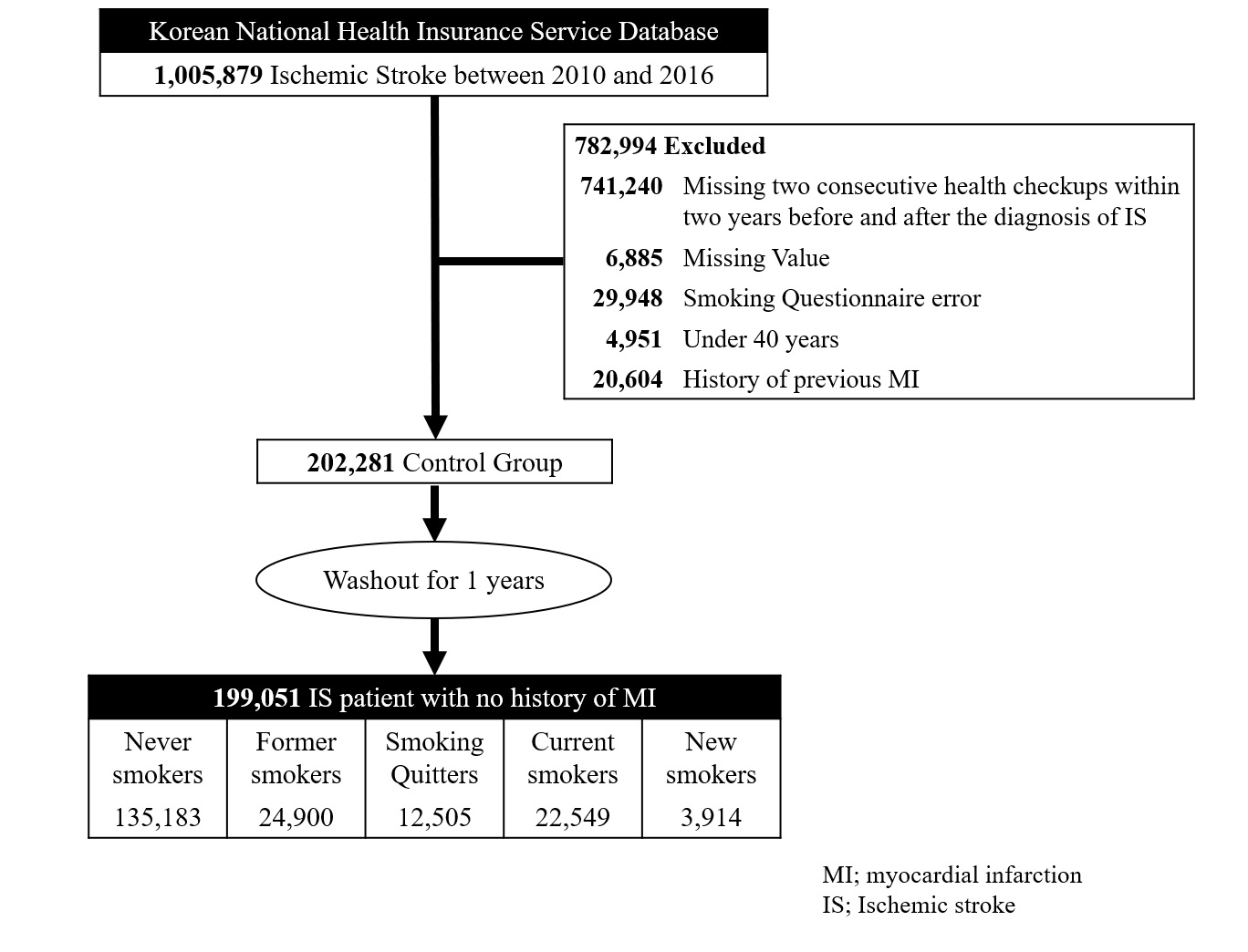

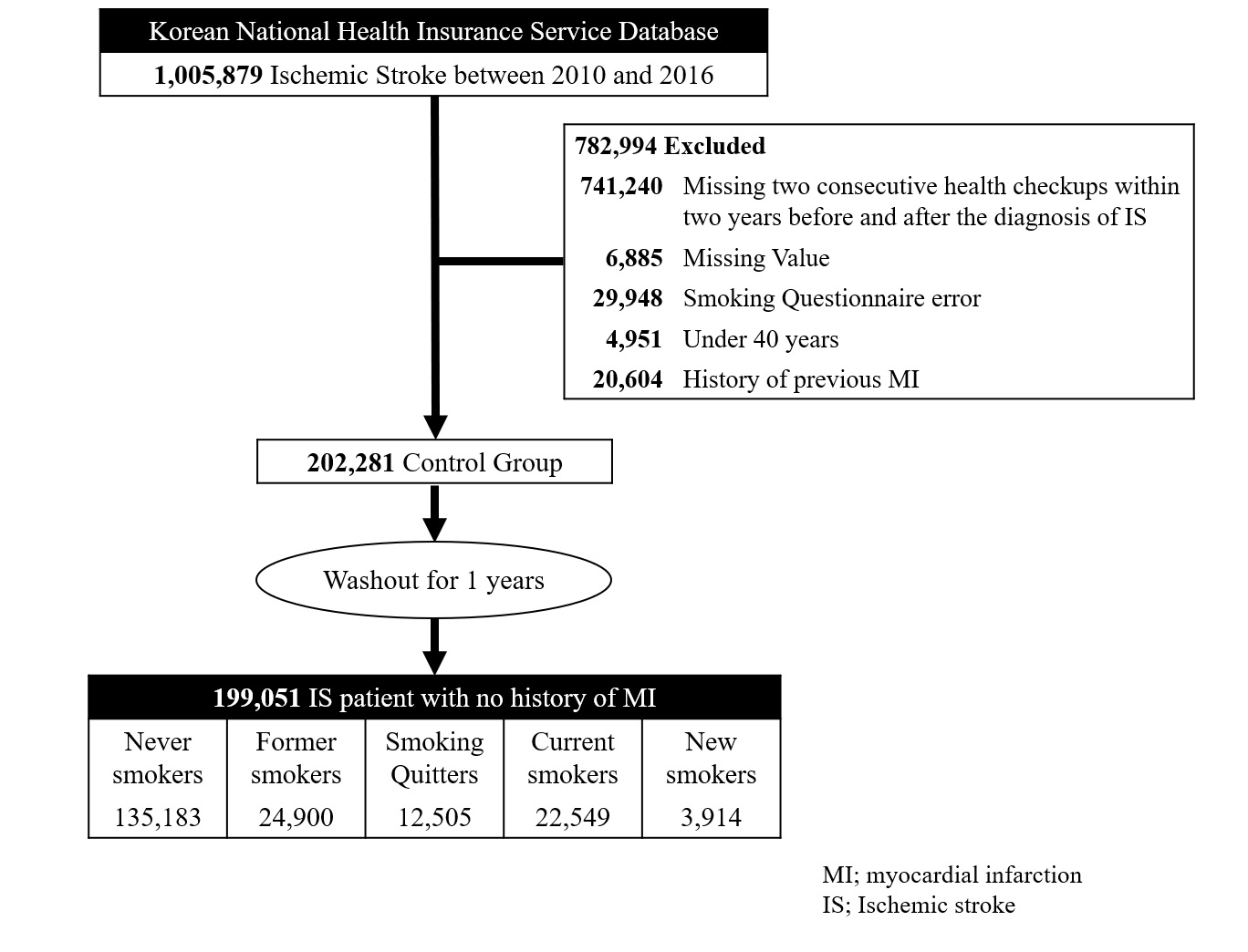

The K-NHIS cohort used for this study consisted of people who underwent a nationwide health checkup between January 2010 and December 2016. We identified 1,005,879 patients newly diagnosed with acute IS in this period. After exclusion according to the following criteria,199,051 patients with IS with no history of MI were included in the study (Figure1).

Results

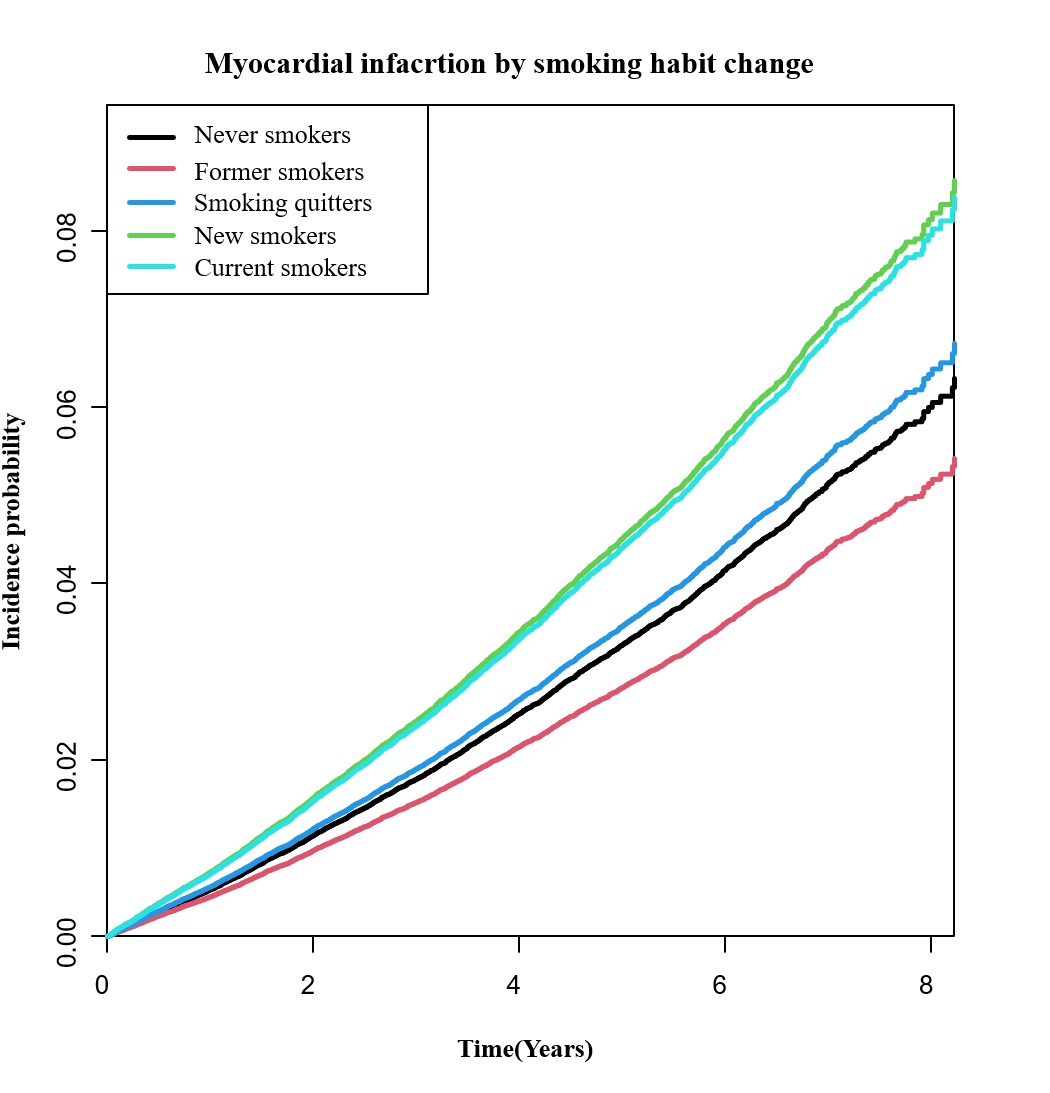

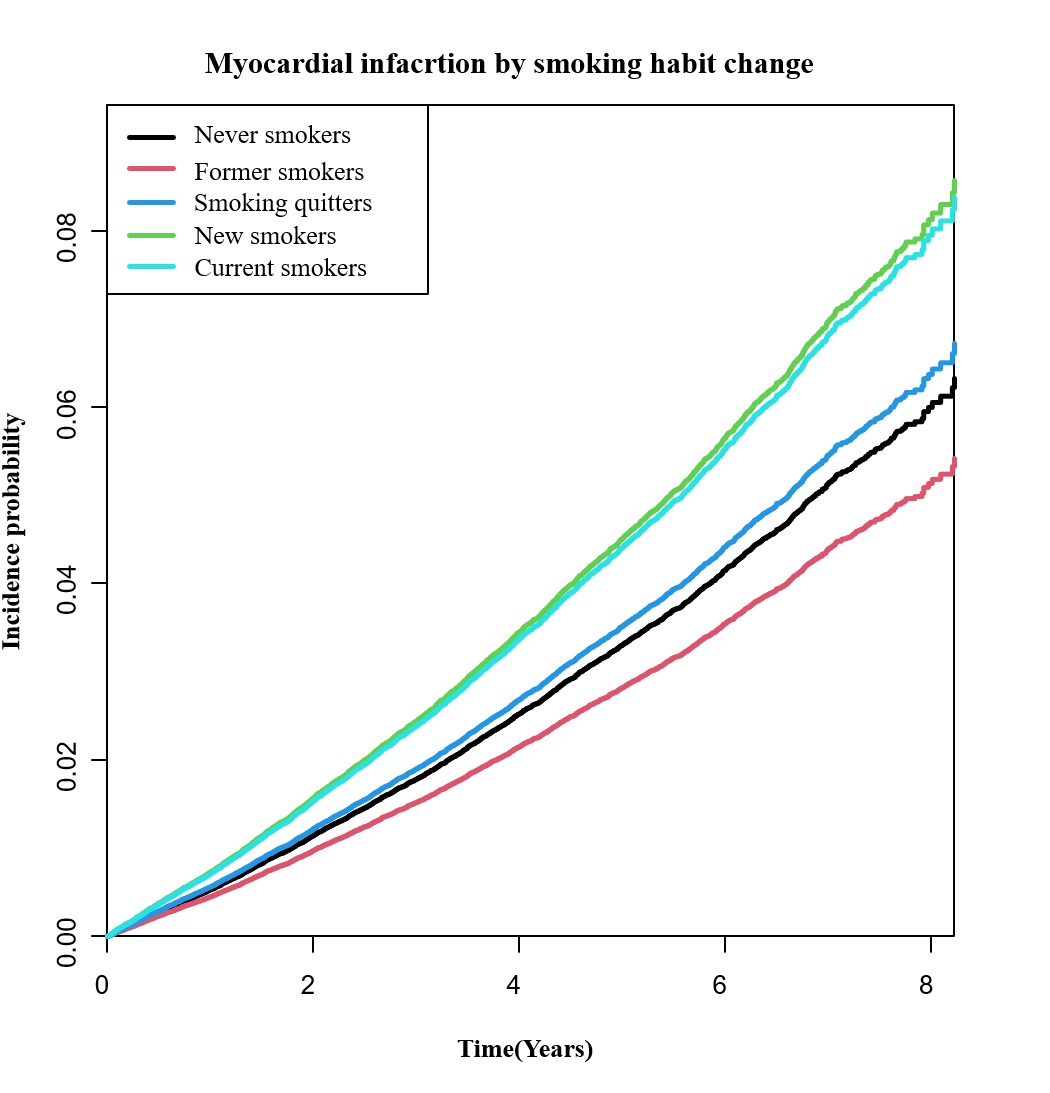

199,051 patients with IS with no history of MI (mean ischemic stroke age 64.2±10.5 years; male, 45.1%) were finally included in the diagnosis. Median follow-up duration was 4.17 person-years(interquartile range 2.61-5.93) and 63,868 (32.1%) patients had a smoking history; median pack-years was 24.03. Patients in the never-smokers group were more likely to be female (78.49%), older, non-diabetic, and consume less alcohol. Out of 26,463 patients who were sustained smokers before the diagnosis of ischemic stroke, 23,472 (85.2%) continued to smoke even after the diagnosis of ischemic stroke.

Conclusion

This study is conducted with the largest population regarding the reports on the incidence of MI in a single race‐ethnic group over a relatively long period of time after IS using a KNHIS big database. In conclusion, smoking quitters or former smokers have a similar or lower rate of MI after IS than the average. Otherwise, current and new smokers had a significantly higher risk of incident myocardial infarction after ischemic stroke. Our results have a crucial clinical suggestion that physicians should actively advise patients to stop smoking, not just to prevent stroke recurrence but to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction.