Lots of interesting abstracts and cases were submitted for TCTAP 2021 Virtual. Below are accepted ones after thoroughly reviewed by our official reviewers. Don’t miss the opportunity to explore your knowledge and interact with authors as well as virtual participants by sharing your opinion!

TCTAP A-004

Presenter

Korakoth Towashiraporn

Authors

Korakoth Towashiraporn1, Treenet Reanthong

Affiliation

Her Majesty Cardiac Center Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand1

View Study Report

TCTAP A-004

Acute Coronary Syndromes (STEMI, NSTE-ACS)

Effectiveness of Intracoronary Eptifibatide Bolus Only on Myocardial Perfusion During Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patient Presented with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Real-World Evidence

Korakoth Towashiraporn1, Treenet Reanthong

Her Majesty Cardiac Center Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand1

Background

Intracoronary thrombus formation during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) results in occlusion of the coronary artery. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) aimed to restore myocardial perfusion of the infarcted-related artery. However, distal thrombus embolization may occur during PPCI and caused further impaired myocardial perfusion. Eptifibatide is the only glycoprotein IIb IIIa inhibitors, which are available and included in the pharmaceutical reimbursement list in Thailand. It is indicated as adjuvant therapy in the current STEMI guideline for the treatment of a thrombotic complication during PPCI. From our knowledge, the conventional administration of eptifibatide nationwide was a double bolus of intracoronary (IC)Eptifibatide only without intravenous (IV) continuous infusion. The advantage of the double bolus only IC Eptifibatide not only easy to use but also reduce bleeding complications as compared to IV continuous infusion. We aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of IC Eptifibatide accompanied by the conventional PPCI.

Methods

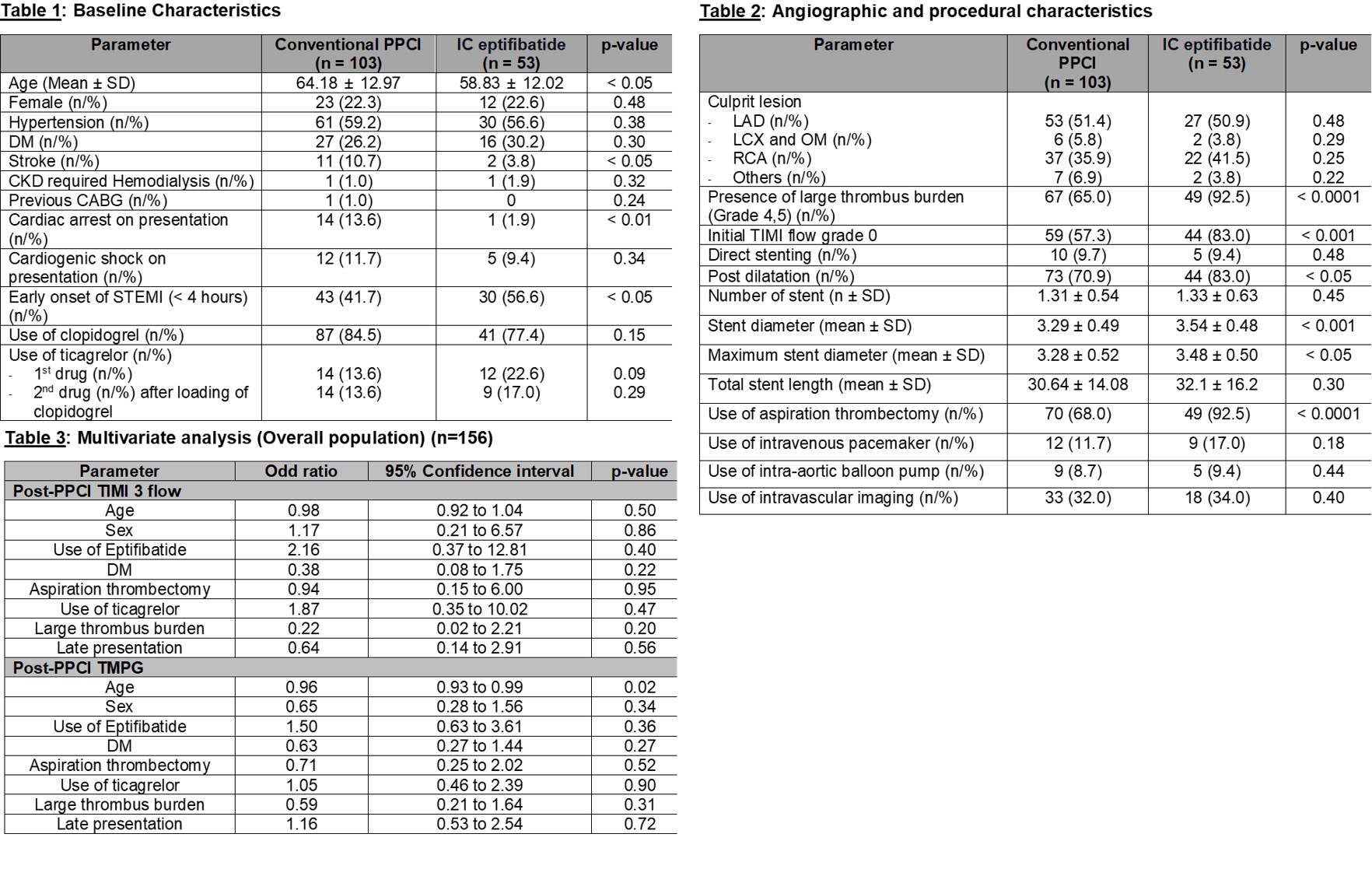

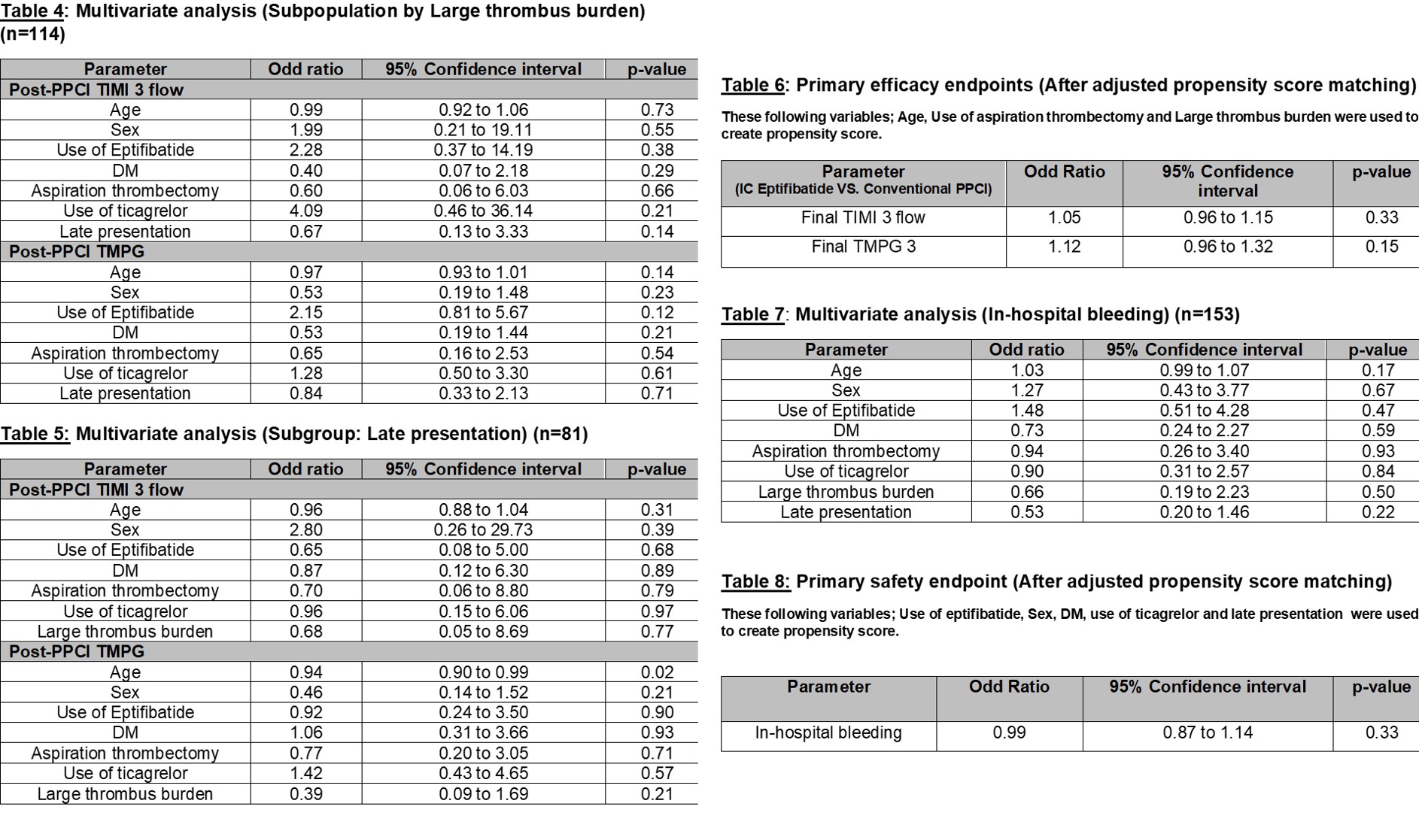

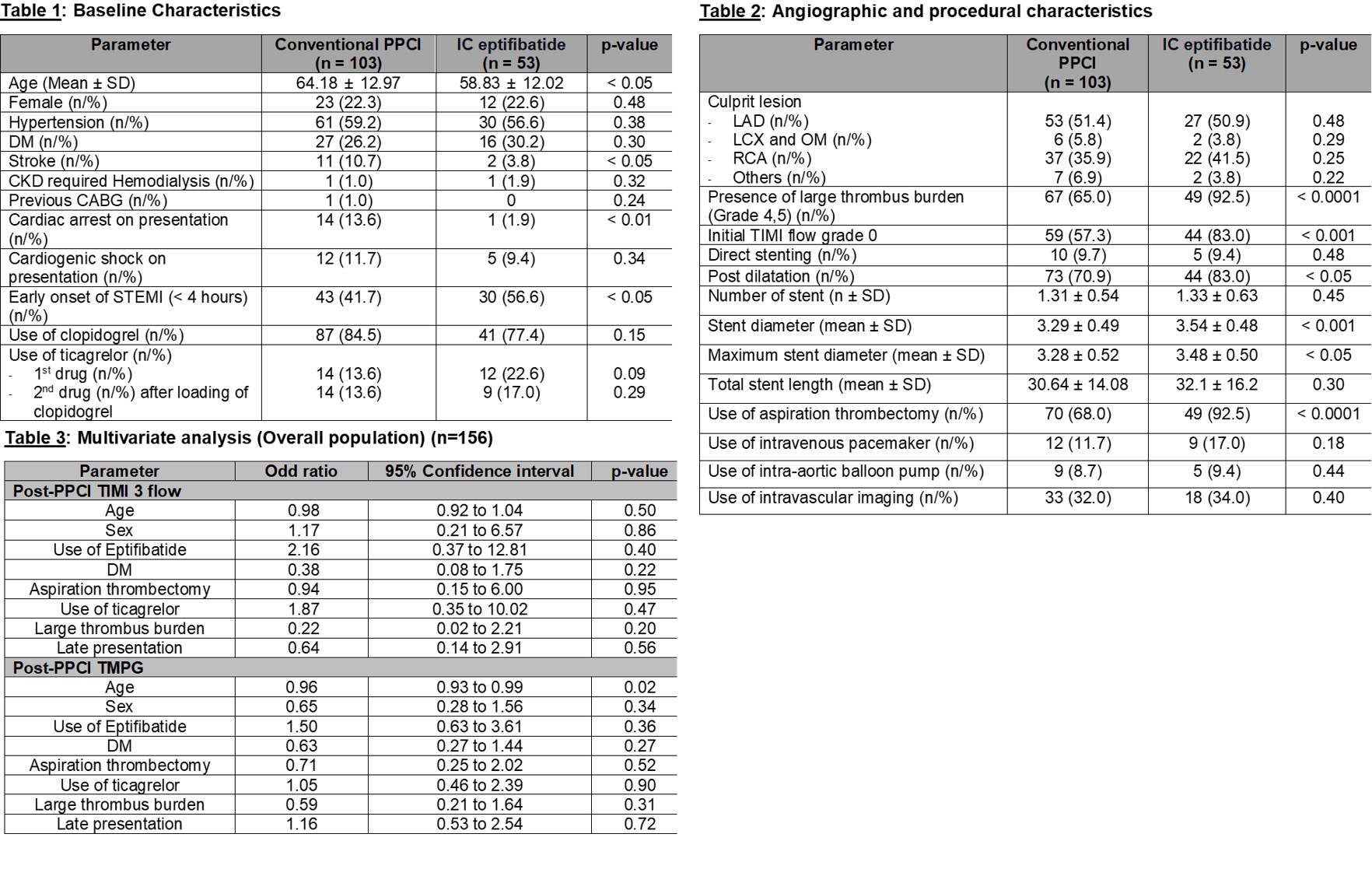

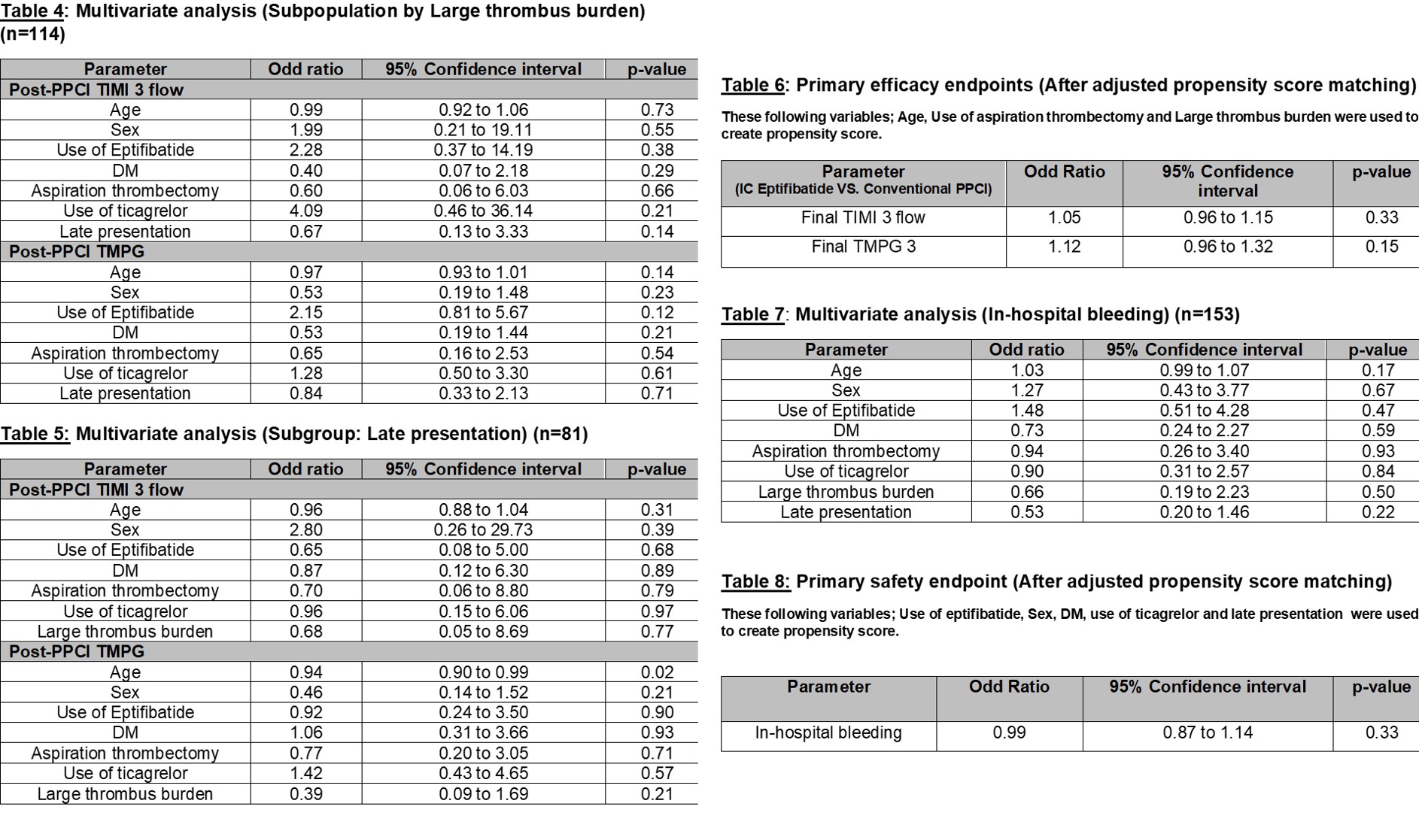

This retrospective study included 156 patients who presented with STEMI and underwent PPCI by a single operator aimed to exclude inter-operator variation that may influence the outcome of PPCI, between August 2015 to May 2020 at Siriraj Hospital, Thailand. The study compared the conventional PPCI group and the IC eptifibatide group. The choice of periprocedural medications (including dual antiplatelet therapy, heparin, IC eptifibatide), coronary stents, and the use of aspiration thrombectomy device was at the operator’s discretion. The primary efficacy endpoints were post-PPCI Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Flow and post-PPCI TIMIperfusion grade (TMPG). The primary safety endpoint was in-hospital bleeding events. We conducted the multivariate logistic regression to compare the outcomes of both alternative interventions. The use of propensity scores was also applied to identify and control for confounding in observed data.

Results

Thirty-five patients were female. The average age was 62.3 ±12.9 years. Of these, 43 patients had diabetes. 46% categorized as early presenters(Total ischemic time < 4 hours). 75% of the patients had a large thrombus burden (TIMI thrombus grade 4-5). Fifty-five patients received IC eptifibatide. The conventional PPCI group achieved post-PPCI TIMI3 flow 92% whereas, The IC Eptifibatide group achieved Post-PPCI TIMI 3 flow 96%. The conventional PPCI achieved post-PPCI TMPG 70% while The IC eptifibatide group achieved post-PPCI TMPG 77%. By the multivariate analysis, IC eptifibatide compared to conventional approach was no statistical difference in term of both probability of improved post-PPCITIMI 3 flow (Odd Ratio (OR) 2.16, 95% Confidence interval (CI) [0.37 to 12.81];p = 0.40) and post-PPCI TMPG improvement (OR 1.50, 95% CI [0.63 to 3.61]; p =0.36) in all populations. Similarly, the results of sub-populations (Large thrombus burden and late presentation) not demonstrated the difference between both outcomes. Moreover, the multivariate models using propensity score, IC eptifibatide showed not statistically significant as the rate of improvement of post-PPCI TIMI 3 flow and post-PPCI TMPG (OR 1.05, 95% CI [0.96 to 1.15]; p =0.33 and OR 1.12, 95% CI [0.96 to 1.32]; p = 0.15, respectively). IC eptifibatide was not increasing in-hospital bleeding (Twelve events in the conventional PPCI group vs. eight events in the IC eptifibatide group (OR 0.99,95% CI [0.87 to 1.14]; p = 0.92).

Conclusion

After adjusted propensity score matching, IC eptifibatide did not statistically significantly improve myocardial perfusion during PPCI with similar in-hospital bleeding events as compared to conventional PPCI. However, when considering the context of a limited resource setting (e.g. a lack of Angiojet thrombectomy and Laser atherectomy in Thailand). On the other hand, Eptifibatide was feasible in almost of catheterization laboratories nationwide. The use of IC Eptifibatide bolus only accompanies by conventional PPCI to achieved better myocardial perfusion was a reasonable option in the setting of PPCI in our country.