Lots of interesting abstracts and cases were submitted for TCTAP & AP VALVES 2020 Virtual. Below are accepted ones after thoroughly reviewed by our official reviewers. Don¡¯t miss the opportunity to explore your knowledge and interact with authors as well as virtual participants by sharing your opinion!

* The E-Science Station is well-optimized for PC.

We highly recommend you use a desktop computer or laptop to browse E-posters.

ABS20191027_0002

| Acute Coronary Syndromes (STEMI, NSTE-ACS) | |

| Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes Among Patients Receiving Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention After an Acute ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Contemporary Single-Center Experience in Multi-Ethnic Asian Population | |

| Hui Beng Koh1, Mohamed Nazrul Mohamed Nazeeb2, Nay Thu Win3, Chee Sin Khaw4, Birry Karim5, Arvin Romero Yumul6, Jayakhanthan Kolanthaivelu7, Kumara Gurupparan Ganesan2, Shaiful Azmi Yahaya2 | |

| National Heart Insitute, Malaysia1, National Heart Institute, Malaysia2, Royal Free London, United Kingdom3, Sunway Medical Centre Penang, Malaysia4, Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Indonesia5, Medical Center Manila, Philippines6, Cardiovascular Sentral Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia7 | |

|

Background:

Acute ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) is a medical emergency, where "time is myocardium", and this continues to be a global health predicament. The prevalence continues to be high particularly with lifestyle becoming more sedentary and the rising prevalence of risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and smoking, to name a few. Patients presenting with STEMI need to be treated as early as possible with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PPCI), lest they run into higher risk of morbidity (such as heart failure) and mortality. And PPCI is known to reduce these events. Nevertheless, these outcomes are unsatisfactorily still prevalent among patients who had received PPCI. This results in not only higher health care burden and cost, but also in loss of productivity. Hence it is prudent to identify, at an early stage, those who are at increased risk of adverse outcomes despite PPCI. In this study we aim to identify the incidence, clinical characteristics and outcomes of inpatient mortality and future admission for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ADHF) among patients successfully treated with PPCI in our setting of multi-ethnic Asian population.

|

|

|

Methods:

This is a retrospective observational analysis of 868 cases of successful PPCI between 2015-2018. Data was collected for background and clinical characteristics on admission, in-hospital mortality and follow up admission for ADHF post primary PCI. Analysis was conducted using descriptive analysis, Chi square test, independent t test, Mann-Whitney, Logistic regression, Cox Regression and Kaplan Meier curve. Outcomes that were looked at were In-hospital mortality and ADHF incidence after PPCI. In all analyses, a P value < 0.05 was considered as significant. Statistics were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics(V.2.5).

|

|

|

Results:

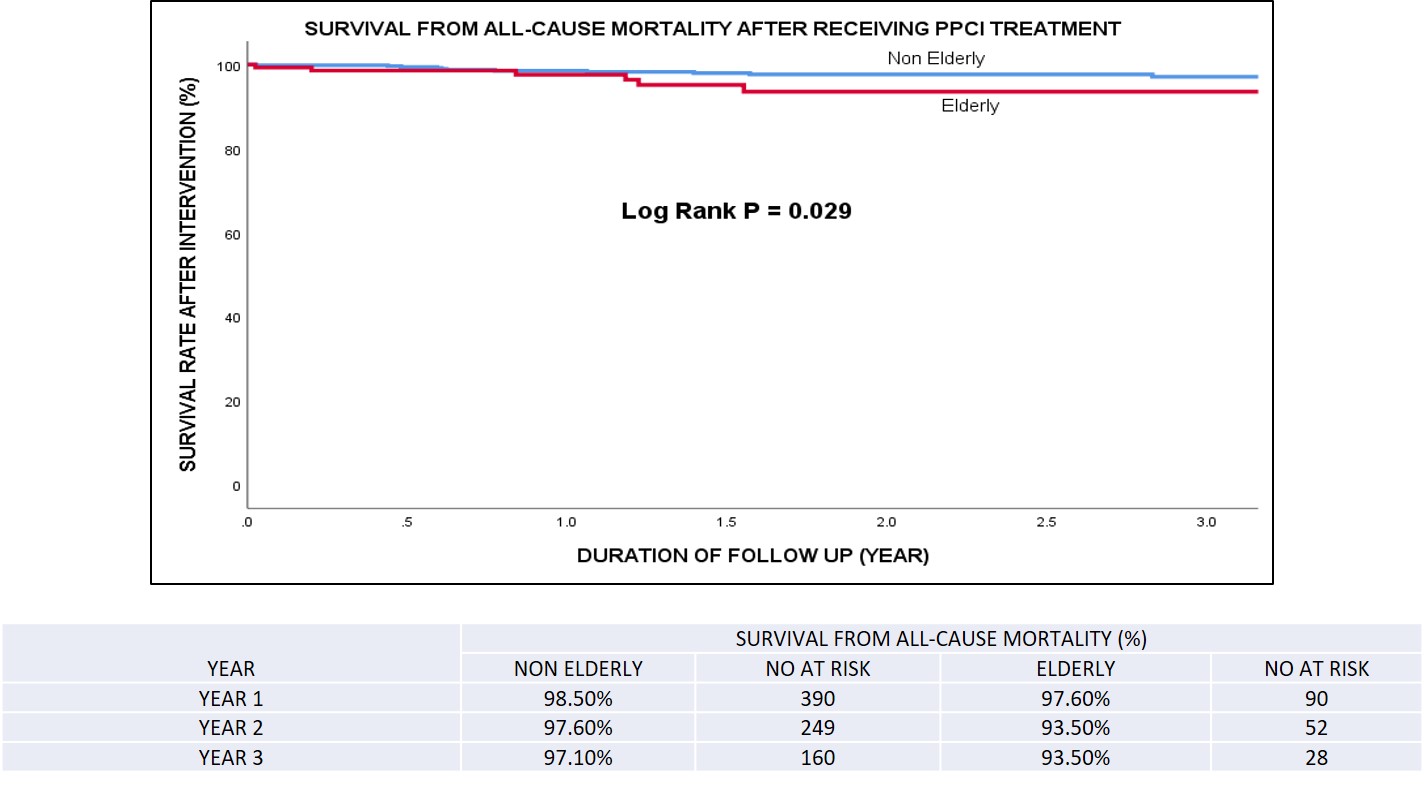

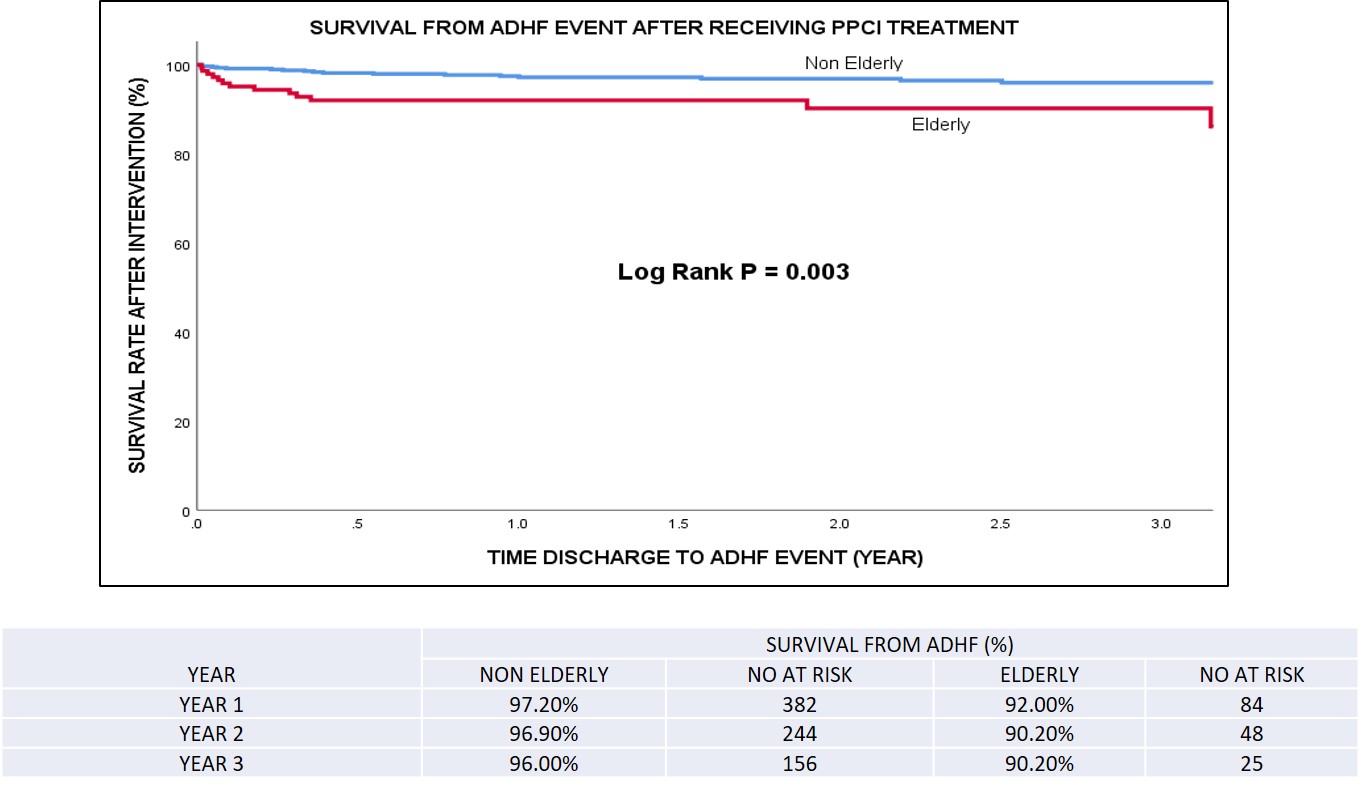

Out of 868 successful PPCI cases, there were 38 in-hospital mortality. Out of 738 cases with follow up, 34 cases presented with ADHF and 18 cases of mortality. The incidence proportion of all-cause mortality among patients with successful PPCI was 2.2 cases per 100 population during median time of follow up 1.5 years, or an average of 1.5 cases per 100 per year. Most were males (86.2%) and were of the non elderly age group (<65 years old) (80%). Patients of Malay ethnicity (54.4%) were the most, followed by Indian (27.4%) and Chinese (15.6%) patients. The risk of in-hospital mortality (among patients with successful PPCI) were significantly greater when they were elderly ¡Ã 65 years old [adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) 2.76; 95% Confidence interval (CI) 1.34-5.68; p-value (p) 0.006], had chronic kidney disease [aOR 4.94; CI 1.57-15.57; p 0.006] and presented with cardiogenic shock [aOR 10.06; CI 4.97-20.35; p<0.001. Risk of ADHF event at follow up were also significantly raised when patients were elderly ¡Ã 65 years old [adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR) 2.47; CI 1.23-4.94; p 0.011], presence of cardiogenic shock [aHR 2.54; CI 1.23-5.22; p 0.012] and when length of stay was > 3 days [aHR 2.87; CI 1.37-6.04; p 0.005]. The incidence proportion of ADHF after successful PPCI was 4.6 cases per 100 population during median time follow up of 1.5 years, or an average of 3.1 cases per 100 per year. Door to balloon and total ischemic times were not seen to exert any significant influence on the in-hospital mortality nor the events of ADHF at follow up.

|

|

|

Conclusion:

Outcomes of in-hospital mortality and ADHF events after successful PPCI were not seen to be influenced by the door to balloon nor total ischamic times, suggesting that contemporary practices of PPCI within the stipulated accepted time frames are adequate and up to standard of care. Elderly patients aged ¡Ã 65 years and those presenting with cardiogenic shock were both significantly associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality and ADHF events at follow up. CKD was associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality but not for ADHF events, while length of hospital stay > 3 days was associated with increased ADHF events but not in-hospital mortality. It is concerning to note that in these elderly cohort (aged ¡Ã 65 years), although successful PPCI was performed, their risk of ADHF events in future began increasing soon after discharge. In terms of all-cause mortality at follow up, the elderly cohort showed an increased mortality risk compared to the non-elderly after 1 year from PPCI. From this observation, it highlights that despite successful primary PCI, we need to place even greater attention to those at higher risk of mortality and ADHF events by executing early optimisation of guideline directed medical therapy to reduce their overall risk.

|

|